A view of the monument at the spomenik complex at Vukovar, Croatia.

A view of the monument at the spomenik complex at Vukovar, Croatia.

A view of the road that leads up to the monument at the spomenik complex at Vukovar, Croatia.

A view of the monument at the spomenik complex at Vukovar, Croatia.

Vukovar

Brief Details:

Name: Dudik Memorial Park (Spomen-park Dudik)

Location: Vukovar, Croatia

Year completed: 1980 (2 years to complete)

Designer: Bogdan Bogdanović (profile page)

Coordinates: N45°19'49.4", E19°01'02.7" (click for map)

Dimensions: Five 18m tall cone monoliths

Materials used: Diorite stone blocks, wood and copper

Condition: Fair, partially restored but still neglected

(VOO-koh-var)

Click on slideshow photos for description

History:

This spomenik is dedicated to the estimated 455 civilians (communists, anti-fascists and other resistance members) who were executed by Ustaše forces at the site of this memorial between July 1941 and Feburary 1943.

World War II

Soon after the invasion of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Axis-aligned forces marched into Vukovar on April 11, 1941, at which point the city was incorporated in the newly created Axis puppet state of the Independent State of Croatia (NDH). Living under the rule of this new Axis controlled regime, which was policed by the notorious Ustaše military force, was brutal and oppressive for many civilians, especially for Serbs, Jews, communists and other dissidents. While in Vukovar in June of 1941, notable NDH politician Mile Budak gave a speech to the Ustaše proclaiming that all Serbs in the NDH should be considered foreigners, openly stating: "...let [the Serbs] know that our motto is: either bow or be removed." It was not long before the Ustaše began to execute those citizens it found to be 'undesirable'. One of the most notorious instances of mass executions in Vukovar was carried out on July 25th, 1941, where a large group of local civilians were killed in retaliation for the killing of an Ustaše soldier by Partisan resistance in the nearby village of Bobota. These civilians and Partisan supporters were snatched from their homes and arrested in the dead of night, stripped of their belongings, given speedy show-trials and then executed in a wooded area on the southern outskirts of town called 'Dudik', a word which literally means in Serbo-Croatian 'grove of mulberry trees'.

As the war continued in 1942, the NDH leadership felt the resistance from Partisan rebels in the Srem region was still not being controlled to an acceptable level. Especially problematic to the NDH was that the Partisans were torching valuable Slavonian wheat fields as a means of starving their enemy. As a result, at the beginning of August 1942, Ustaše Provost Marshal Viktor Tomić was sent to Vukovar to aid in controlling the situation, with orders to work toward expelling the ethnic-Serb civilian population. One of the first actions Tomić made as soon as he arrived in Vukovar was to restrict access to all telephone and telegraph services, while also instituting a strict curfew. This ensured no outsiders would be aware of the actions he was to take and effectively made the city's residents prisoners in their own homes. From this point, not only were Serbs, Jews and other persons unwanted by the NDH expelled, but hundreds more were also arrested and imprisoned without trial, then subsequently executed at the Dudik groves. By the end of that month of August, Tomić was unexpectedly called by the NDH leadership to assist with controlling the nearby city of Sremska Mitrovica, but not before executing well over 100 additional civilians for the accused crime of being rebel sympathizers.

Photo 1: Partisan troops during the Liberation of Vukovar in 1945 [source]

However, before Tomić left, he ordered all civilian prisoners still in captivity in Vukovar to be transported to the death-camps at Jasenovac. Vukovar was finally liberated from the Ustaše fighters on April 14th and 15th of 1945, after the breaking of the Sremski Front, by 1st and 3rd Yugoslav Partisan Armies, along with assistance from Soviet Red Army forces (Photo 1). After accounting for the dead at the end of the war, it is roughly estimated that about 455 civilians were executed at Dudik during the course of the war, yet some suspect the number to be much higher. They were all buried in 9 mass graves among the mulberries around the area of this memorial. The Dudik mass graves were exhumed in 1945 shortly after the end of the war (Photo 2), overseen by the State Commission for establishing the Crimes of the Occupying Forces and their Collaborators. Of those specifically accounted for during the exhumations, 348 were Serbian, 71 were Croats and 2 were from Bosnia.

Photo 2: Exumations of mass graves at Dudik in Vukovar, 1945 [source]

Spomenik Construction

After Vukovar's liberation in April of 1945, some of the mass graves at Dudik were exhumed during war-crimes investigations and the remains of roughly 400 bodies were found. Many of these remains were respectfully re-interred at a new memorial crypt built at Victims of Fascism Square (Trg žrtava fašizma) in Vukovar. Then, in 1959, a set of memorial pillars were erected at the Dudik site to honor the WWII massacre victims, which also marked the 40th anniversary of the Communist Party in Yugoslavia. However, after the ethnic tensions caused by the Croatian Spring during the late 60s and early 70s, Yugoslav authorities felt that some of the more unambitious WWII monuments might reinvigorate the region's sense of "Brotherhood & Unity". As a result, in 1975 a new committee was formed to redevelop the Dudik memorial site. The committee made the decision that Serbian architect Bogdan Bogdanović would be a suitable artist for the project, so Bogdanović was contacted personally by the Mayor of Vukovar. Bogdanović agreed to take on the commission.

Photo 3: A sketch by Bogdanović of the memorial site

Photo 4: The original 1959 monument, w/ the new one under construction behind it, 1979 [source]

During the planning phase of the creation of the memorial, Bogdanović had a number of ambitious ideas that evolved over time, including having the monument adorned with carved monsters as well as symbolically burying sections of the constructed monument underground (neither of which ever came to pass). However, the idea of the central element of the complex being a series of cones was a theme present in nearly all of his concept sketches for the project (Photo 3). When the physical construction of the monument began, Bogdanović employed skilled stonemasons from Pirot, Serbia and local coppersmiths who had recently constructed the roof for a Catholic church in Vukovar. Also during the construction of Bogdanović's work, the original Dudik memorial pillars from 1959 were removed from the site (Photo 4). Finally, after two years of work, the spomenik complex was opened to the public during a ceremony on June 26th, 1980. The memorial consisted of a 1-hectare sized complex whose central element was five 18m tall stone-block and copper cones. The lower half of the cones are constructed of stacked Bosnian diorite blocks, while the upper half of the cones are covered in copper sheets over a wooden frame. These cones are set within the grove of mulberry trees where the mass graves were found. A large sunken amphitheatre was also included just in front of the cones which could accommodate up to 3,000 people. Just to the north of the cones lay 27 large diorite stone blocks carved into a stylized 'boat' shape, laid out in a seemingly random pattern.

As far as the 'random' placement of these stone 'boats' around the memorial site is concerned, many sources recount a story that Bogdanović settled on the location for these positions by gathering a group of local Vukovar children and instructing them to arrange themselves around the mulberry grove as if they were ships. Sources relate that his words to the children were, "Boys and girls. Here something terrible happened that should never be forgotten. Look at the boats. They are the boats of your future." After the children were situated, Bogdanović marked these places as the location for the stones. Also, it is important to note that not only were victims from the Dudik executions interred at this site, but also fallen fighters from the 5th Vojvodina Partisan Brigade and some Soviet Red Army fighters who perished nearby during the battles at the Sremski Front in December of 1944.

The June 26th, 1980 inauguration of the Dudik Spomen-Park was said to have been attended by nearly 10,000 people (Photo 5), an event that included many speeches and cultural performances. Sources estimate the cost of the project was roughly 17 million dinars, which conversion sources [PDF] roughly estimate would be 578,000USD in 1980 (or 1.8 million in 2019 dollars). Future plans for the Dudik site included the creation of an exhibition hall, restaurant, visitors center, etc, but these were never realized, most likely a result of Yugoslavia's economic troubles of the 1980s.

Photo 5: A view of the 1980 Dudik monument inauguration [source]

Yugoslav Wars

For many years, this was a popular and active memorial in the days of Yugoslavia. However, with the onset of The Croatian War of Independence in the early 1990s, this monument began to fall into disrepair and destruction. During the Battle of Vukovar, which was an 87-day long siege waged by the Belgrade-led Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) starting on August 25th, 1991, the spomenik complex was significantly damaged, with many of the cones left nearly or completely destroyed by shells and bullets. In addition, many of the site's original mulberry trees were cut down or leveled. During the siege, roughly 90% of the city of Vukovar was destroyed and well over 1,000 civilians were killed. The Battle of Vukovar was by far the largest conflict during the 1990s wars in Croatia. A heavily bombed water tower (Photo 6), hit by shells nearly 600 times, later became an enduring memorial symbol for the city's dramatic siege.

Photo 6: Water tower severely damaged during the Battle of Vukovar.

Meanwhile, the Dudik monument itself also sustained intense damage during the conflict. The neighborhood in Vukovar where the monument was located, Mitnica, was a place of much division and experienced some of the most significant bouts of fighting during the 1990s battles around the city. Academic researcher Brit Baille recounts in her 2019 paper that Bogdanović felt the destruction of his Dudik monument was a direct targeting, stating that it was "revenge against me" by the JNA troops on behalf of Serbian President Slobodan Milošević. In the years leading up to the Yugoslav Wars, Bogdanović was a vocal critic of Milošević's nationalist policies, which resulted in Milošević vilifying Bogdanović in the popular press. As a result, Bogdanović subsequently fled Serbia and in 1993 went into self-exile in Vienna.

Present-Day

In the years after the Yugoslav Wars, the Dudik site was left largely neglected in a state of disrepair. During the mid-2000s, attempts were made by the local authorities to construct a football complex on roughly 5,000 square meters of the northeast corner of the Dudik memorial area. Such plans were met with harsh objections by the local ethnic-Serbian community of Vukovar who instead advocated for the Dudik memorial to be rehabilitated, however, despite these objections, the football complex was completed on the Dudik site in March of 2008. The football complex was constructed for the football club HNK Mitnica, which is a club consisting of Croatian veterans from the 1990s Croatian War of Independence. The football club uses the ruined Vukovar water tower as their symbol.

Despite the construction of the football complex within the space of the Dudik memorial space, the ethnic-Serbian community of Vukovar eventually achieved their goal of restoration of the monument when the Dudik Memorial Park Renewal Initiative was launched in 2013, organized by Ars Publicae Heritage Program. During the restoration project, which cost roughly 300,000 kuna (40,000 euro), the copper and wood-frame tops of the cones were fully repaired and brought to their original condition (Photo 7). Meanwhile, weeds covering the complex were cleared out and the landscaping was refurbished. While the Dudik site no longer draws significant crowds (as Vukovar is off of most standard touristic routes, while also often being perceived as an ethnically tense and divided city), it is still very notable that efforts were coordinated to repair and refurbish the memorial in this way. Very few of the old spomeniks across the Balkans have seen this level of rehab after falling into such disrepair, neglect and destruction.

Photo 7: The cones of the Dudik Memorial prior to restoration, 2012

Plaques, Engravings and Graffiti:

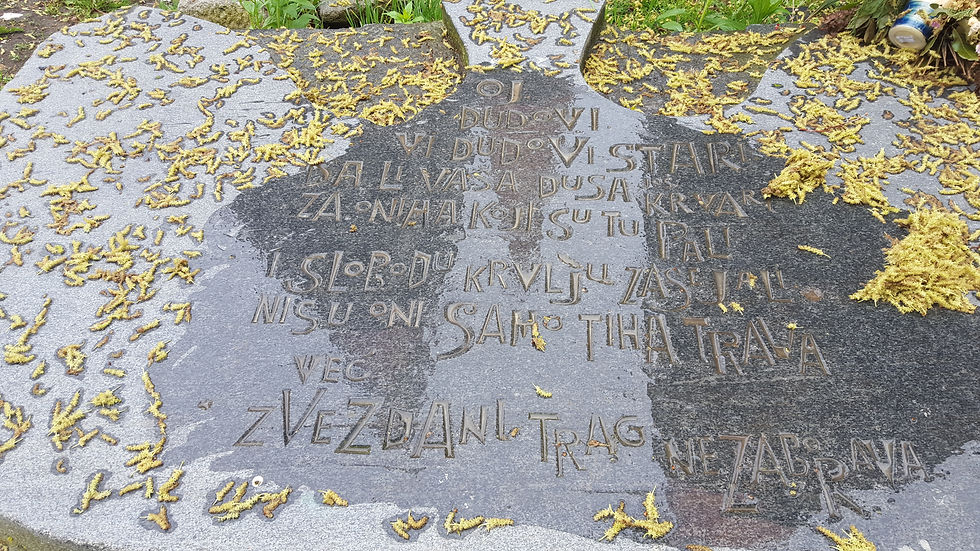

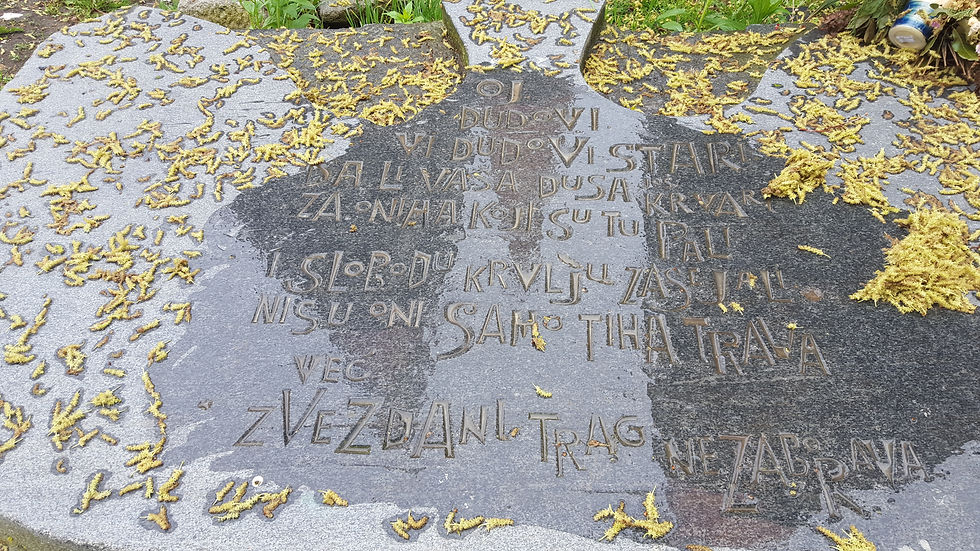

At the center of the group of cones is a flower-like stone which is inscribed with poetic verse. The verse is written in the ornate and difficult to read script-style that is standard on nearly all of Bogdanović's memorial works. The inscription on this stone (Slide 1), which lays flat on the ground among the cones, roughly translates from Croatian to English as:

"Our mulberry, old mulberry, if your soul bleeds for the fallen and the freedom their blood sowed, know that they are not only silent grass, but also the forgotten star trail."

A modern-day view of one of the engraved stones at the spomenik complex in Vukovar, Croatia.

A historic 1980s era view of some of the engraved stones at the spomenik complex in Vukovar, Croatia which no longer exist.

A historic 1980s era view of some of the engraved stones at the spomenik complex in Vukovar, Croatia which no longer exist.

A modern-day view of one of the engraved stones at the spomenik complex in Vukovar, Croatia.

Slideshow

In addition, on the north edge of the series of 'boat stones' there are several engraved stones sitting among the tall overgrown grass. Many of these stones are every damaged and it is not clear if this position was their original orientation, as a historic photo (Slide 2) shows a very different configuration. The largest among them is a large rectangular white stone (Slide 3) which bears a large engraving which translates from Croatian to English as:

"Memorial Park Dudik"

Meanwhile, there are three additional flat rectangular stones laid out in a row in this same area. The middle of these stones contains a poetic stanza written by poet Đorđe Radašić, which can be seen in Slide 4. This roughly translates from Croatian to English as:

"Companions, in the time to come, if they ask, tell them we are buried in the ground, eternally keeping guard."

Then, the western-most engraved stone of this group (Slides 5 & 6) contains a series of inscribed names of groups and organizations who contributed to the creation of this memorial site. At the bottom right-hand corner of this stone is an inscribed dedication date for the monument complex (Slide 7). It reads as, translated from Croatian to English, as:

"This memorial park was opened on the 26th of June, 1980, commemorating 60 years since the 2nd Vukovar Congress of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia."

The last of the three engraved stone among this group is the eastern-most stone which can be seen in Slide 8. This inscribed stone translates from Croatian to English as:

"Traveller, who is going into the future, stop and at this spring get drunk on the clear water, the beauty of freedom, and the love of those who gave their lives for it"

Furthermore, there were also some large engraved stone plaques set in front of several of the mulberry trees (Slide 9). These now appear to be absent, as I could not locate them during my most recent visit to the site.

Symbolism:

When it comes to interpreting the Dudik monument, there are several perspectives with which to approach the work. One interpretation of this memorial is that the five stone/copper cones at this spomenik are intended to represent the five torches of the emblem of Yugoslavia, where each single torch represents one of five ethnicities of Yugoslavia: Croatian, Serbian, Macedonian, Slovene and Montenegrin. Extending this interpretation, it may also serve to highlight that the massacre which took place here was a tragedy for (and assault towards) all ethnic groups in Yugoslavia. Interestingly, despite a 6th torch being added to the emblem in 1963 to represent Bosniaks, a 6th torch was not included here, despite it being constructed 17 years after that addition. Therefore, either this interpretation is incorrect or the memorial's creator, Bogdan Bogdanović, made an active decision not to include a sixth cone structure.

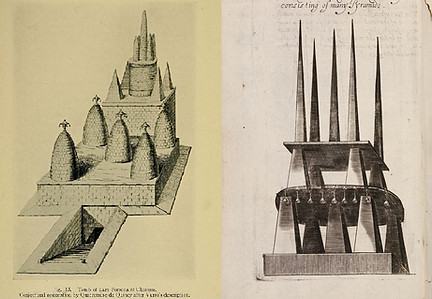

Another interpretation of the five cones is that their design is an attempt by Bogdanović to invoke ancient styles of design and architecture into his work. Some historians have asserted that the memorial is meant to mimic descriptions of the highly mythologized lost tomb of the Etruscan king Lars Porsena (Photo 8) which was supposedly destroyed in 89BC by Roman general Cornelius Sulla in what is today central Italy. The historic description of the tomb, which describes five tightly arrange stone pyramids, could very well be the basis for the memorial, as not only has Bogdanović been consistently known to include obscure ancient mythology into his work, he is also known to have potentially included Etruscan motifs in other monuments he constructed (such as the one at Novi Travnik for example). In fact, if you look at concept drawings that Bogdanović made for the Vukovar spomenik (which can be seen in the Historic Images slideshow below), some look startlingly similar to the imagined concepts for the ancient tomb seen in Photo 8.

Photo 8: Historical imagined concepts for the appearance of the tomb of King Lars Porsena.

In fact, in an interview where Bogdanović is discussing his methods and thinking behind the design and atmosphere created by the cones at the Vukovar spomenik, he is quoted as saying:

"I like to believe that this is a strong space... a space in flight, fugitive. And it seems to me that the visitor is rather like an adventurous traveler returning returning to the remote past and, to his surprise, comes across the secret unexplained mausoleum of Lars Porsena... but when I saw [images of] Porsena, I had already decided on the [Dudik] mausoleum... [and] strictly speaking [Dudik] has no roof (as Porsena does), but its five points support a heavenly canopy instead, and this is the main difference from the Etruscan model."

However, while Bogdanović concedes here that his Vukovar cones have no physical roofs or canopies, differing them from the classical artist interpretations of Porsena, the well-defined stone-metal boundary separating the upper and lower halves of the cones very much acts as an symbolic roof or canopy. As a result, despite his denials, I suspect Bogdanović was overtly and deliberately attempting to recreate Porsena, but, not wanting to reveal his direct inspirations, he did so in an indirect fashion employing symbolism and subtle changes to make it his own creation.

Photos 9 & 10: Conceptual sketches of Bogdanović of Dudik Memorial

Yet another interpretation of the sculptures here at the Dudik Memorial complex is that Bogdanović intended the site to resemble the remains of a long lost sunken or buried city. Sources relate that Bogdanović would often be found sketching his architectural creations in a state of dilapidation and decay while making a point to emphasize to students in his lectures at the University of Belgrade that over the course of time, all structures fall into ruin. In fact, when he first encountered the monument he had built at Novi Travnik after the Bosnian War and found it in ruins, he openly advocated that it NOT be restored and left in a degraded condition it has fallen into.

Interestingly, looking at conceptual sketches for the Duduik Memorial (Photos 9 & 10), many of them show a structure that looks almost as if it contains subterranean components to it, as if Bogdanović intended to build a significant amount of the memorial underground, then bury it on purpose. In a 2019 paper by academic researcher Britt Baillie, she relates a quote by Bogdanović on this very concept:

"I began to draw contours of buildings and cities, I sketched them buried by a flame and ash rain … only the pinnacles protruding from the earth … whoever saw the granite and copper cone on Dudik, could rightly imagine a whole city buried underneath."

While this may have been a fantasy Bogdanović imagined, from all sources I have seen, this was NOT actually done. In addition, thinking about the cones as remnants of a sunken or buried city allows one to look at the Šajka boats from a new perspective -- these vessels now become unknowing witnesses to the world that once existed below them, unable to fathom the forces which consumed it. In a similar way, those who visit Dudik have little ability to fully internalize the victims who lay below the feet nor comprehend the brutal ways in which they were killed.

In reference to these 27 large carved boat stones -- as mentioned above, these are meant to represent 'Šajka' (or chaika) boats, which were historical wooden boats used all the way back to the 1200s in shipping goods and traffic on the Danube and other water-courses across the Balkans (Photo 11). In addition, groups of these boats collected into flotillas (or Šajkaši) were instrumental for the ethnic-Serbian fighters of the Military Frontier in defending against Ottoman invaders from the 1500s up until the 19th century. Their inclusion here by Bogdanović is certainly meant to draw attention to Vukovar's historic connections to and dependence on the Danube River. When asked about the symbolism of the boats, Bogdanović was quoted as saying:

"I wanted to mark death, but I couldn't do it. I had to celebrate life... and so I chose the Šajka [boat]."

Photo 11: Painting of šajka boats on the Danube River by Jacob Hoefnagel, 1597

Status and Condition:

This spomenik has been through a great deal over the last three decades. Currently, it is in fair condition, but it suffered a significant amount of degradation and destruction during the Yugoslav Wars/Homeland War, as this area experienced intense conflict, fighting and bombing. Many of the elements of the complex suffered bullet holes and many of the cones suffered holes with their wooden/copper tips broken and fragmented. This spomenik sat abandoned and forgotten in this degraded state for many years. Then in 2014, 300,000 kuna (40,000 euro) was allocated for the renovation of the monument by Croatia's Ministry of Culture after requests by the Ars Publicae Heritage Program, who organized the restoration. During this restoration, which began in 2014, the wooden/copper tips of all five cones were replaced and refurbished back to their original condition (Photo 12). However, while the renovation is officially completed, as of 2016, many more original elements of the memorial still remain absent and un-restored. In addition, this memorial complex has been added to the 'Register of Cultural Goods of Croatia'.

Photo 12: A view of the reconstruction of the Dudik Memorial, 2015

Photo 13: A view of a commemorative ceremony at the Dudik Memorial, 2017

Meanwhile, despite this refurbishment and renovation, there are no directional or promotional signs leading visitors to this spomenik. In addition, this site contains no informational or interpretive signs which might relate to visitors the cultural and historic significance of the memorial. Also, I found no honorific wreaths, candles or flowers laid here, so, it is not clear to what levels locals regularly come to pay respects to the site. And while local commemorative events such as Anti-Fascist Struggle Day (June 22nd) and Vukovar's Liberation Day (May 10th) continue to utilize this memorial complex as a site for their commemoration events, they are not as hugely attended as they were pre-1990s, only attracting a few dozen people (Photo 13). However, these events are significant in the sense that they are a multi-country participation, generally between Croatia, Serbia and BiH (but sometimes other countries as well) which is generally organized by the Union of Anti-Fascist Fighters of Vukovar and Srem.

Additional Sites in the Vukovar Area:

This section explores additional Yugoslav-era historical, cultural and memorial sites in the greater area around Vukovar that might be relevant to those already interested in the Dudik Spomen-Park or other Yugoslav sites. Sites which will be examined here include the monument at the Victims of Fascism Square in Vukovar, as well as the Worker's House (Radnički dom).

The Worker's House/Grand Hotel

During the Yugoslav-era, a large yellow Baroque-style building in the town center of Vukovar (Slides 1 - 3) was a significant political historic site for the country's ruling party, because it was here in June of 1920 that the Second Congress of the Socialists Worker's Party of Yugoslavia gathered (Slide 4). It was during this meeting that the new official name of the organization "The Communist Party of Yugoslavia" (KPJ) was decided upon. It was at this meeting that the revolutionary faction of the KPJ took control of the group, leading the historians of Yugoslavia to point to this meeting (known as the 'Vukovar Congress') as the beginning of the momentum that led to the group's revolution in the wake of WWII. The building that this Congress was held in is significant in its own right, having been built in 1897 by famous architect Vladimir Nikolić. It was originally called the 'Grand Hotel', but in 1919 it turned into a laborer-run cooperative called the Worker's House, which explains why the KPJ Congress was held at this site.

Worker's House/Grand Hotel - Slideshow

During the heated conflicts of the Yugoslav Wars in the early 1990s, the Worker's House building was severely damage and was reduced to a state of near total devastation (Slide 5). However, as of 2013, the entire exterior of the building has been restored by a joint project with the City of Vukovar, the Government of Croatia, the EU and the UN (Slide 6). Located in the town center of Vukovar right on the Vuka River waterfront, the exact coordinates for the building are N45°21'03.3", E19°00'09.3".

Square of Victims of Fascism Monument

Located in the center of the Square of the Victims of Fascism in the, just north of the town center of Vukovar, is a circular marble monument (Slides 1 - 3). A large inscription on the front of the monument reads, when translated from Croatian to English, as:

"Here are buried the mortal remains of 388 victims of fascist terror brought from Dudik, 155 fighters of the 5th Vojvodina Strike Brigades and 62 fighters of Red Army killed on December 8 & 9 of 1944, during their journey over the Danube and their liberation struggles for Vukovar."

I was not able to determine the author or year of creation of this monument. Its exact coordinates are N45°21'24.0", E18°59'38.6".

Monument at Victims of Fascism Square - Slideshow

And Additional Sites of Interest:

-

Vukovar Municipal Museum: Just north of the city center of Vukovar is the town's Municipal Museum. Housed in the opulent 18th century Baroque manor called "Castle Eltz", this museum contains thousands of artifacts and explores the history, art and culture of Vukovar. The castle was significantly damaged during the region's wars of the 1990s, but it has been completely rebuilt and rehabilitated. The museum's official website can be found here, while its exact coordinates are N45°21'16.7", E19°00'01.0".

-

Monument to Fallen Fighters in Vukovar: In the center of Vukovar along the south banks of the Vuka River, right in front of what was then the "Workers' House", a monument was erected in 1955 commemorating 10 years anniversary of the liberation of Vukovar (Photo 14). Created by Sisak-born sculptor Želimir Janeš [profile page] (along with assistance by his then teacher Antun Augustinčić), the form of this monument is a set of three bronze figures, with a central wounded figure being carried by two others on either side. This motif of "carrying the wounded" was a common and important theme in Partisan memorial art. This was one of the most important monuments in Vukovar during the Yugoslav-era, with it being depicted as a landmark feature of the town on countless postcards. However, the monument was severely damaged during the Yugoslav Wars and later removed completely during the mid-1990s, with all traces of its previous existence expunged. The current location of the sculpture's mangled bullet-marked remains is unknown. Today, a bust of French fighter Jean-Michel Nicolier sits near its former location. The coordinates of this original location are N45°21'03.9", E19°00'08.7".

Photo 14: Two vintage postcard views of the Monument to Fallen Fighters in Vukovar

Photo 15: A recent photo of the derelict Hotel Dunav in Vukovar [source]

-

Hotel Dunav: Yet another site in Vukovar that was an important Yugoslav-era landmark in the community was Hotel Dunav (Photo 15), a grand accommodation complex situated right at the confluence of the Vukar River and the Danube River (which is what "Dunav" translates into). Unveiled in 1980 and built by the architect team Matija Salaj and Zvonimir Krznarić, the hotel shows signs of early postmodernism, with its attempt at employing traditional architectural motifs in new contexts, most notably the cascading red roof atop the hotel tower. Hotel Dunav stood as an important symbol for Vukovar up until the Yugoslav Wars, which left the facility utterly devastated. For many years now, the hotel has sat derelict and unused (though it is important to note that the hotel's most extreme facade damages were indeed repaired). However, in 2019, news sources reported that the hotel was bought by a Swiss company. Initially slated to re-open in 2023, as of yet, Hotel Dunav still remains closed. The exact coordinates for the hotel site are N45°21'05.3", E19°00'16.6".

Directions:

From the city center of Vukovar, head east towards the Danube River and turn right onto Ulica Bana Josipa Jelecica. Follow this about one-quarter kilometer, then turn right at a business called Club Quo Vadis onto Dakovacka Ulica (see Google StreetView location here). Next, take your very first left onto Prosina Ulica, and then in about 100m take the left fork onto Ulica Marije Juric Zagorke. Follow this residential road for about 1km, and it will leave the neighborhood and turn into a dirt road just past an intersection. Follow this dirt road about 100m and you will see the spomenik on the left. There is a gravel parking lot along the road, parking can be made there and the spomenik can be easily walked to along a short trail. In the Google StreetView here of where the neighborhood road turns into the dirt road, the spomenik can easily be seen in the distance. Exact parking coordinates are N45°19'49.2", E19°00'59.8".

Click to open in Google Maps in new window

Historical Images:

A historic view from the 1980s era of the monument at the WWII spomenik complex at Vukovar, Croatia.

A historic view from the 1980s era of the monument at the WWII spomenik complex at Vukovar, Croatia.

Construction blueprints from the 1970s of the spomenik complex by Vukovar, Croatia.

A historic view from the 1980s era of the monument at the WWII spomenik complex at Vukovar, Croatia.

Slideshow

Selected Sources and More Information:

-Croatian Wiki article: "Spomen-park Dudik"

-Jadovno article: "Oj dudovi vi dudovi stari da li vasa dusa krvari"

-Brit Baille paper: "The Dudik Memorial Complex: Heritage as ‘Resistance’ in a Contested City"

-Lajčo Klajn book: "The Past in Present Times: The Yugoslav Saga"

-Gojko Jokić book: "Jugoslavija - Spomenici Revolucije"

-Friedrich Achleitner book: "A Flower for the Dead"

-Znaci Archive article: "Vukovar u oslobodilačkom ratu"

-Patrick Naef paper: "La Yougonostalgie et les monuments fantômes de l'espace post-yougoslave" [PDF]

Comments:

Please feel free to leave a message if you have any comments, if you have any questions, if you have corrections or if you have any additional information or insight you feel might be appropriate or pertinent to this spomenik's profile page.